Table of Contents:

- The Four Questions That Changed Animal Behaviour

- Stamp Dawkins and Why Watching (Closely) Is Still Revolutionary

- Principles of Observational Study Design

- Why Observe?

The study of animal behaviour is unlike many other areas of biology. The scale at which we look at it is inherently about watching. Of course, behaviour may ultimately be rooted in the genome. But, what we often find most interesting about it exists in the here and now: a lot of the time what is, or at least could be, right in front of our eyes.

In the early days of my seal research project, I read Observing Animal Behaviour by Marian Stamp Dawkins (2007). This book profoundly shaped how I approached the work. The bulk of my research involved careful observation. My project focused on postnatal females, whose every movement during lactation carries an energetic cost. As capital breeders, they fast throughout nursing, relying entirely on energy stored as “capital” prior to giving birth. Observing consistent micro-movements during rest revealed an intriguing phenomenon. To explore this, I developed a rest-specific ethogram and a key point annotation system, producing a quantitative model of fidgeting behaviour. Across a small sample size, repeated in separate years, fidgeting patterns appeared consistent within individuals and showed correlations with energy management and stress responses previously characterised along a reactive axis.

All of this was extrapolated from hours of footage, filmed years earlier, of focal seals set against the quaint backdrop of distant mother–pup pairs, nuzzling in the drizzle on a remote Scottish isle. I realised, somewhere between my tenth hour of seal footage and my fourth cup of machine coffee, that I actually loved the watching. The stillness, and the slow discovery of it all.

Although Dawkins’ writing definitely clarified the design of my observational study, what stayed with me most was her defence of observation itself. Dawkins highlights how, in the rush to control for variables through complex experiments, we can sometimes overlook this crucial phase. Yet, approached with a bit of intellectual alacrity, observation remains one of the most robust and non-invasive ways to understand animals in their natural context.

Somewhat inevitably, observing animals carefully has naturally been at the heart of ethology. As Darwin reflected in his autobiography (1958, p. 140): ‘Some of my critics have said, “Oh, he is a good observer, but has no power of reasoning.” I do not think that this can be true, for The Origin of Species is one long argument from beginning to end.’ Observation, Darwin reminds us, is inseparable from reasoning, and I would argue that any observation worth the notebook it’s recorded in is, in itself, an intellectual exercise.

Dawkins reminds us of this essential truth, and in doing so pays homage to the pioneering ethologist Niko Tinbergen, whose four questions remain central to how we think about animal behaviour.

The Four Questions That Changed Animal Behaviour

In his landmark 1963 paper “On Aims and Methods of Ethology,” Tinbergen proposed that to fully understand any biological trait, and particularly why an animal behaves as it does, we must ask four distinct but complementary questions:

Causation (Mechanism):

What triggers the behaviour? What are the underlying physiological and neurological processes?

This question focuses on the immediate causes of behaviour; how the animal’s nervous system, hormones, genes, and sensory input interact to produce a response. For example, a drop in body temperature might prompt huddling for warmth, or the sound of a conspecific’s call could trigger a territorial display.

Development:

How does the behaviour develop or change over the individual’s lifetime?

Some behaviours are present at birth (innate), while others are learned through experience or social interaction. Some behaviours in juveniles may elicit better parental care, whilst others may develop after maturity to facilitate this from the other side.

Function (Survival Value):

What is the behaviour for? How does it improve the animal’s chances of survival or reproduction?

This asks how a behaviour contributes to the animal’s fitness. Behaviours that improve chances of finding food, avoiding predators, attracting mates, or caring for offspring are more likely to persist in a population.

Evolution:

How did this behaviour evolve over time across species?

This traces the evolutionary history of the behaviour. Similar behaviours seen in related species may have a common ancestral origin. Differences might reflect adaptations to new environments. This perspective connects behaviour to the broader tree of life, showing how it is shaped by long-term processes like natural selection and genetic drift.

These questions span levels of explanation, from the immediate to the ultimate, and they still serve as a foundation for behavioural science today (Bateson and Laland, 2013).

But Tinbergen also gave the warning, “contempt for simple observation is a lethal trait in any science.” Before you jump into experiments, you must first watch, with a view to these questions.

Stamp Dawkins and Why Watching (Closely) Is Still Revolutionary

As Marian Stamp Dawkins argues in Observing Animal Behaviour (2007), observation is far from a passive or outdated approach. Like any experiment, observational studies demand careful design and interpretation, as well as a keen awareness of potential biases.

One of the core challenges in studying behaviour is its inherently changeable and continuous nature. Unlike fields such as chemistry or other biological sciences, which benefit from standardised units like pH or volts, behavioural science lacks a universal metric. Behaviour unfolds fluidly over time and context, varying not just between individuals but within individuals across days, situations, and internal states (Dawkins, 2007). Experimental methods often aim to control or eliminate this variation. In contrast, the nature of observational studies is such that they must work with it, by minimising irrelevant noise to recognise patterns relevant to the research question.

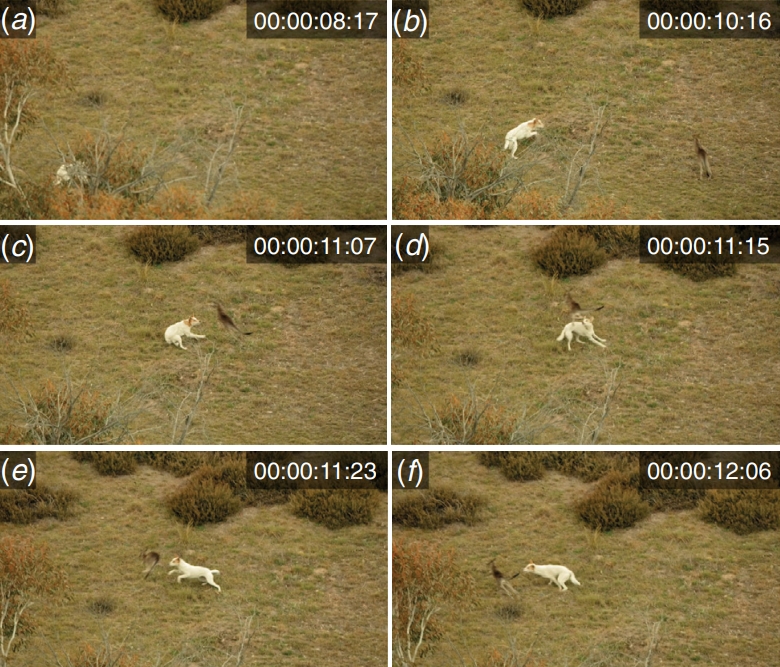

Dawkins reminds us that a skilled observer can detect subtle, meaningful patterns that may be invisible to experimental methods. And these days, aided by high-resolution video, and remote sensing techniques, and observational data can be analysed with the similar quantitative muscle as experimental results.

Principles of Observational Study Design

Good observational design follows principles just as robust as any lab-based study. As Grafen and Hails (2002) and Dawkins (2007) outline, there are key pillars to rigorous observation:

1 . Replication and Independence

As Grafen and Hails (2002) argue, it’s crucial to identify the correct statistical unit and avoid pseudo-replication in observational studies (e.g. individual, group). Simply observing more animals doesn’t automatically mean you have more valid data points. One of the biggest challenges in observational studies is ensuring the independence of each observation. Sources of non-independence, such as the influence of conspecifics, shared past experiences, or repeated observations of the same group, can distort results. It’s essential to look out for these factors, as they could introduce bias.

Stamp Dawkins gives the example of observing a flock of sheep. Say you are investigating the response of sheep to an auditory stimulus: splitting them up into independent units by separating them from one another may help with statistical analysis but might not be biologically valid. Instead, a better approach would be to treat the flock as a single data point and then seek to compare it with independent flocks from other locations. The more independent replicates you can gather, the more power you have to test your hypothesis effectively.

2. Control of Confounding Variables

Confounding variables can obscure or distort cause-and-effect relationships. Identifying these variables doesn’t mean you must eliminate them, but rather balance or randomise them across replicates to ensure they don’t bias your findings. In other words, these factors should affect each replicate equally. This can be achieved through randomisation or balancing of data points such as:

- Randomly selecting focal animals in the field or from video footage using tools like grid sheets or coordinate generators.

- Using a single trained observer, or where that’s not possible, ensuring repeated observations by multiple observers to verify that data is being interpreted consistently.

- Where feasible, maintaining observer blindness, so that those recording the data are unaware of key variables like treatment group or hypothesis being tested. Full blindness is often difficult in field studies, especially when traits like sex or age are easily visible to a trained observer but it’s still important to minimise observer bias wherever possible.

3. Blocking and Matching

The final core principle of good experimental design is to minimise unwanted sources of variation. When studying animals in natural or semi-natural settings, variation is unavoidable. Animals will differ in their genetics and environments, and unlike in laboratory settings, it’s often neither possible nor desirable to try to control everything.

Instead of eliminating background variation, an effective strategy can be to block it or match within it. The idea is to account for known sources of variation by structuring your observations accordingly. Let’s say you want to know whether male or female southern elephant seals are more active during peak breeding season, and whether this varies between rocky and sandy breeding sites. you wouldn’t want to simply compare all males at the rocky site with all females at the sandy site. That would confound site and sex. Instead, you could:

- Block by site, and then within each site, compare males and females. That way, you’re controlling for environmental and social conditions specific to each location.

- Alternatively, you might match males and females by age, size, or reproductive status within each site to make the comparisons more meaningful.

- Then, compare those patterns between sites to assess whether the same sex shows higher activity in both settings, or whether the effect of sex on activity is site-dependent.

Mirounga leonina, southern elephant seal at different sites. Image credits: McGaughey (2013) – left; Kim et al. (2020) – right.

If you’re especially concerned with individual differences, you could go further and track the same individuals across multiple time points or contexts. For example, observing their behaviour in the morning versus the evening, or during early versus late breeding season. This approach allows each individual to serve as their own control, helping to filter out a large amount of natural variation and enabling you to focus on what actually changes. In my seal project, I tried to capture these individual differences by blocking observations to look for patterns over time. I examined whether behaviour changed with time since the pup’s birth and whether patterns were consistent from year to year. This approach helped to filter out natural variation, and allowed each mother to act as her own reference point. Of course, I’d be naive to claim that this study had enough data points to draw definitive conclusions. What I could do, however, was leverage footage recorded for a different project on seal reactivity and, applying these principles, repurpose it to explore fidgeting behaviour.

At this point, it becomes clear why many behaviourists may opt for experiments. It’s much easier to manipulate conditions and remove confounding variables, which may be essential for some questions. But observation is not nearly as passive as it may seem. Much can be done before the researcher ever decides to experiment, and well-designed observational studies can control for many of the same variables.

There’s another reason why observation matters, something I hadn’t explicitly considered before reading this book. It fosters understanding. Watching an animal closely builds an intuitive sense of its responses, its personality. This kind of insight is essential for good animal welfare science. A scientist who has sat with a species for hours on end, will likely treat their subjects with more compassion, and will likely ask better questions of them.

As Manning and Dawkins (2012) put it: “Someone who has acquired a good knowledge of animal behaviour will better understand the welfare and needs of the focal species.” In a time when ethical research is rightly a top priority, this matters more than ever.

Why Observe?

As Dawkins puts it, it’s hypothesis-generating, but also hypothesis-testing, when paired with the right questions.

So if find yourself wondering what to do with your animal behaviour project, maybe don’t rush to the lab or the code. Sit still. Watch. Take notes, and develop good questions.

And to any behavioural ecologists who might have stumbled across this post, seriously check out Observing Animal Behaviour by Marian Stamp Dawkins. I know I’ll certainly be returning to it again and again.

References

Bateson, P. and Laland, K.N. (2013). Tinbergen’s four questions: an appreciation and an update. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28(12), pp.712–718.

Darwin, C. (1958), Barlow, Nora (ed.), The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his granddaughter Nora Barlow.

Dawkins, M.S. (2007). Observing Animal Behaviour. Oxford University Press.

Grafen, A. and Hails, R. (2002). Modern Statistics for the Life Sciences. Oxford University Press.

Kim, B.M., Lee, Y.J., Kim, J.H., Jin Hyoung Kim, Kang, S., Jo, E., Seung Jae Lee, Jun Hyuck Lee, Young Min Chi and Park, H. (2020). The Genome Assembly and Annotation of the Southern Elephant Seal Mirounga leonina. Genes, [online] 11(2), pp.160–160. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11020160.

Manning, A. and Dawkins, M.S. (2012). An Introduction to Animal Behaviour (6th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

McGaughey, I. (2013, October). May cause offence to feminists, vegetarians, and conservatives. Outgrid: Macquarie Island & Antarctica. [online] Available at: https://outgrid.weebly.com/macquarie-island–antarctica/may-cause-offense-to-feminists-and-vegetarians

Pollock, T.I., Hunter, D.O., Hocking, D.P. and Evans, A.R. (2022). Eye in the sky: observing wild dingo hunting behaviour using drones. Wildlife Research. doi: https://doi.org/10.1071/wr22033.

Tinbergen, N. (1963). On Aims and Methods of Ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20(4), pp.410–433.

Tobias, J. and Seddon, N. (2000). Territoriality as a paternity guard in the European robin, Erithacus rubecula. Animal Behaviour, 60(2), pp.165–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2000.1442.

Twiss, S.D., Cairns, C., Culloch, R.M., Richards, S.A. and Pomeroy, P.P. (2012). Variation in Female Grey Seal (Halichoerus grypus) Reproductive Performance Correlates to Proactive-Reactive Behavioural Types. PLoS ONE, [online] 7(11), p.e49598. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049598.

Title image credit: Pollock et al. (2022)

Leave a comment